Bullock's Egyptian Hall is long gone, and the travelling days of the Medusa are, also, over. Darkened by time and by the artist's injudicious admixture of bitumen to his pigments, it is now deemed too fragile to leave the Louvre. It might not exactly be showbusiness, these days, but still it pulls the crowds. Even the most determinedly quick-stepping tourists tend to pause before it, if only for a moment, as though somehow troubled by this enigmatic image of marine struggle under storm- darkened skies.

The Shipwreck of the Medusa (1819)

Theodore Gericault was born 200 years ago and died at the age of 31. The Medusa is one of only three paintings by his hand to have been exhibited during his own lifetime. It is absent from the magnificent retro-spective of his art at the Grand Palais, but that is no bad thing. The 300 or so works assembled prove that Gericault was far, far more than the tragically unfulfilled prodigy, the one- painting master of popular myth. He is confirmed as a giant of art, a colossus standing on the far shore of modernity.

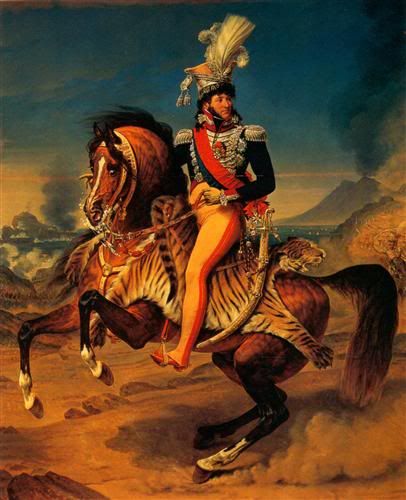

The Grand Palais show opens on a void. You enter a long, long gallery, at either end of which, facing one another, hang a pair of pictures originally exhibited as pendants at the Paris Salon of 1812. One is the tame Equestrian Portrait of Murat, Roi de Naples, painted by Baron Jean-Antoine Gros, one of the chief propagandists of Napoleonic France. The other is Gericault's first large painting, his Charging Chasseur. The distance between the paintings reads as a metaphorical device, a way of measuring the gap that separated Gericault from the other painters of his time.

Gros' Murat is an effete, ineffectual symbol of French imperial might. Posing astride his horse, in his gilded military finery, he is more fashion-plate than embodiment of martial valour. What Gros did, albeit in-voluntarily, was to create an image of Napoleonic propaganda strained to breaking point. Gericault would cultivate this sense of dissonance, of a conflict between the message demanded by convention and that actually delivered, and virtually make it his signature. The Charging Chasseur was the first portent of his ability to unsettle.

Murat, Roi de Naples by Jean-Antoine Gros

A member of the elite troop known as the guides de l'Empereur, mounted on a wildly leaping horse, brandishes his sabre and prepares to go into battle. An image, apparently, of heated engagement, Gericault's Charging Chasseur was favourably received by contemporary critics. ''In this soldier,'' wrote one, ''the artist has represented the Hero''. But Gericault's Chasseur is an odd kind of hero. He seems strangely at odds with the over-excited horse on which he sits. His expression is sombre, distracted. Suspended on the edge of war's chaos - painted, by Gericault, as a red hell full of swirling cannon smoke and charging bodies - he is lost in contemplation. As the French historian Jules Michelet tellingly observed, ''il fait la guerre en pensant''; he makes war while thinking. Gericault's soldier-philosopher, assailed by doubts, contains the seeds of subversion. It represents the beginnings of Gericault's apostasy from the ideals of Napoleonic France.

As the Salon of 1812 opened, more than 1,000 miles to the East, Napoleon's army had begun its long, miserable retreat from Moscow. By the time Gericault came to paint his next ambitious subject picture, for the Salon of 1814, the Empire had fallen and Louis XVIII was seated shakily on the French throne. While most of his contemporaries pointedly abandoned military subjects, Gericault contributed an extraordinary image of national defeat, the Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle.

Under a threatening sky, and isolated in one of those bleak, cramped landscapes that Gericault so often painted, the soldier casts an anxious backward glance as he beats his retreat. It is hard, nowadays, to appreciate how strange, how troublingly innovative this vast canvas must have seemed at the time of its creation. It occupied no recognisable genre: it was not a portrait of any individual; it did not depict a heroic episode in French history, but the opposite.

The Charging Chasseur (1812)

It is as if the painter has massively enlarged one of those monstrous foreground details in a conventional Napoleonic battle painting - one of those images of dying or despairing figures that would be obligatorily redeemed, in French imperial art, by the consoling presence of Napoleon himself, issuing commendations as he passed serenely on his way. Yet that is just what Gericault has omitted. In his hands, French narrative art literally falls apart. It suffers what might be termed a semantic crisis: its forms may survive, but as fragments, isolated in contexts that rob them of their accustomed meanings.

More moving, in some respects, than his military set-pieces, are Gericault's less well-known portraits of French soldiers. The Three Mounted Trumpeters that he painted in 1814 appear out of mist like troubled ghosts. His Carabinier gazes fixedly to one side as if lost in a daydream. Gericault painted these anonymous sullen remnants of Napoleon's grande armee with fantastic attention to the details of military uniform, to the glow of gold threads or the dull sheen of a breastplate, but in the absence of any sense of celebration - of heroic deeds, of glorious feats performed - this reads as a form of pictorial melancholy. Gericault's wonderful descriptive abilities heighten what becomes, in his art, a desolate sense of discreteness. People and things no longer mean, they no longer exist in significant relation to one another. They simply are, and are isolated. It is hard not to put this clumsily, but there is an awful sense of apartness in Gericault's art.

The Medusa is often thought to be Gericault's finest work because in it - or so the argument runs - he managed to overcome the habit of vacillation that left many of his other major projects unfinished. Yet, in the light of this show, it is equally possible to argue that he was least true to himself in that painting - that by conquering the tendency to fragmentation, to incompletion, that was so strong in him, he produced a vast oddity.

Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle (1814)

Consider the works that pre- date it, painted by Gericault during his brief stay in Italy in 1817. His theme was the race of riderless horses held every year at the close of Carnival in Rome, a primitive event whose origins lay in the animal games of antiquity. Gericault's most finished Barberi Race oil sketches are them-selves possessed by bestial energies. Men and horses strain every sinew, struggling in spaces whose tight cropping intensifies the sense of dark, unruly forces barely confined. If this is Neoclassical art - made so by its Italian setting, its choice of a subject that harks back to antiquity and in its distant, convulsive resemblances to the Parthenon frieze - it is Neoclassicism gone wild, untethered both from stylistic and symbolic restraint. If Gericault's men and horses can be said to be emblematic at all, they read as emblems of a mysterious, irresistible will to violence. Perhaps recognising this, the artist abandoned his plans to enlarge these works: although, in fact, the story of the Medusa was no more suited to such aggrandisement.

French painting is set adrift by Gericault. The straining figures, the passions and the energies that were there from Poussin to David, have been retained (and intensified), but something fundamental has been lost: the framework of shared cultural beliefs, of moral and political and religious precepts, that gave them a focus.

Perhaps it is appropriate that Gericault's most famous painting should have as its subject a group of people who have themselves been unmoored, who float helplessly and without bearings on an open sea. Yet still there is something self-destructive and terminal about the Medusa. The story Gericault illustrated on such a grand scale was a tawdry real-life tale of maladministration, corruption and man's inhumanity to man. The heroic style of his painting, and its references to the art of the past, seem as incongruous as its sheer size: it is both Deluge and Last Judgement, though enacted in an ethical and spiritual void. It is a grand nar-rative painting whose failure to deliver an uplifting, publically comprehensible statement announces the death of the very tradition it occupies.

Mounted Trumpeters of Napoleon's Imperial Guard (1814)

Alfred de Musset provided the most succinct account of the sense, in post- Napoleonic France, that the world had been drained of significance: ''Napoleon gone, human and divine power were re- established, but belief in them no longer existed.'' Gericault gave visible form to this loss of belief while eschewing the theat-rics, the hysterical paraphernalia of nightmare that are found in Goya, to whom he seems closer than to any of his French contemporaries.

His studies of severed heads or amputated limbs, executed in the course of work on the Medusa, intro-duce a new register of tragic feeling into Western art. Painted exquisitely, these carefully arranged composi-tions - a pile of arms, a a pair of heads on a bloodied cloth - should be grotesque but are, instead, poignant. They represent a strange mutation of the classical tradition of figure painting; they are, in a sense, late additions to the genre of oil studies from the nude model; versions of the academies produced by artists for centuries, but sadly mutilated. They announce a different and heretical conception of the human body: no longer the engine of ennobling action, but a thing, an object like any other. Gericault, whose despondent realism is imbued with tremendous gravitas, understood the misery of facts.

As fine, in their way, are the paintings of the insane that date from his last years. They were probably commissioned by a specialist in the study of ''monomania'' to illustrate his theories, but Gericault, as usual, exceeded his official brief. He painted his deluded subjects with immense tenderness and respect - his style, here, is reminiscent of Titian, of Hals, and of Velazquez - and a clarity of attention that reads as a form of identification. They are not (and this too sets Gericault apart from Goya) dramatised or caricatured in any way. They are reminiscent of the portraits of Napoleonic soldiery he had painted earlier in his career: images of disturbed and anonymous individuals, each isolated in void space. Perhaps Gericault's sympathy for these people was understandable. When the world loses its meaning, insanity can seem as logical a response as any.

Andrew Graham Dixon

18-10-1991

http://www.andrewgrahamdixon.com/